|

There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.

Maya Angelou

It’s an old story from the 90s.

Many may not have heard it. Some who may, would have forgotten. Others, may have just ignored.

So, I have to retell it.

With the hope that this time you hear – hear with all your heart and soul.

As a Kashmiri Hindu, it is all the more important to retell our stories now when there is a malicious and perverse attack to erase and distort our history and rewrite it to project the muslim atrocities as a freedom struggle and not as an Islamist jihadi movement (for what it is). Our counter narrative is being chipped at, slowly and steadily, by the Kashmiri muslims, our own intellectuals, and minority leaning political parties. Our barbaric genocide is being discounted as Jagmohan's / center govt's ruse and the Kashmiri muslims are being painted as the victims of Indian atrocities. Difficult as it may be because of a dispersed community to voice our protest, it has never been more important in our 5000+ year old existence to speak out and speak up.

This series is an attempt to share our narrative- our stories and struggles with the new world. - one story at a time.

As a child of around 11, I was angry at something. Angry, I had marched out of the lunch as it was being served in the kaenie (living room). Dashed through the mud stairs to the first floor of my house, pulling at the dried straw sticking out from the walls. Stomped through the richly carpeted neel kuth (blue room) that had a design of intersecting hexagons on the blue ceiling. Big French windows ran across one complete side of the room and opened to the daab (wooden balcony). Angry, I banged open the carved, walnut window. The delicate frame and the multicolored panes shook violently for a while and brought me back to the present – did I break any of the glass?

Thankfully no.

Assured, I stepped back on the daab.

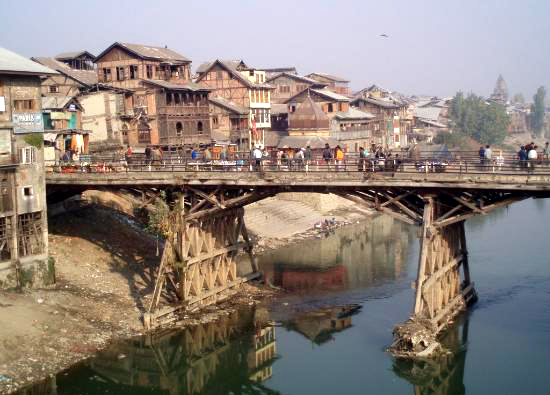

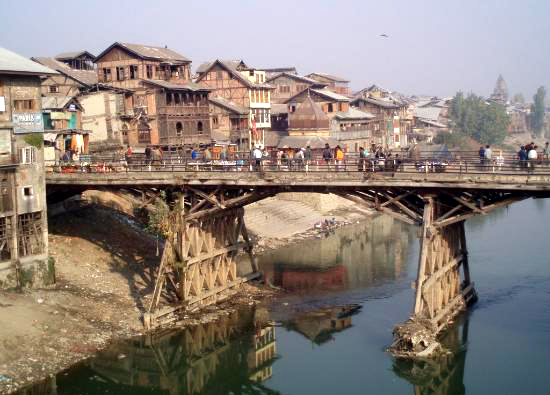

In front of me, Jhelum flowed in all its glory. A mass of quietness plodding through a noisy city. The boat women from the house boats were washing clothes in big iron chillumachis (broad buckets) at the yarbal, the river bank. The carpet makers next door were weaving their song in the carpet. From our side of the daab, one could hear the constant thak-thak as the loom opened and closed, and the shuttle scurried from one end of the loom to another. The white minaret of the nearby mosque seemed to stoically observe the scene from a distance. Though the idgah was just in the next lane, the half-a-minaret was the only part of the mosque visible from my house.

Two big drops raced along my cheeks and splashed on the weathered planks of the daab, creating dark grey dots in the otherwise grey wood. Still angry and now defiant, I paced towards the forbidden side of the five-generation old daab; the floor planks had cracked from years of weathering and were yet to be replaced. “No one cares for me even if I fall.” I cried loudly hoping for some attention from the people downstairs. The noises from down continued unaware of what I thought was an outright crisis. Just to be safe, I quickly placed my hands on the wooden railing of the daab. Mushrooms had grown on the railing yet again.

When I had first seen the mushrooms growing in a crack in the wooden railing, I had excitedly reported it to my mother, “Can we cook them?”

“Throw them away. Not all mushrooms are edible… these could be poisonous” My mother had replied.

I didn’t eat them, though it took me a while to throw them. “So beautiful” I remember feeling, touching their velvety skin, breaking them bit by bit, and flinging them in Jhelum.

Removing the defiant mushrooms was now a routine activity.

“Are you trying to eat my house, you evil mushrooms?” I flung the pieces in Jhelum. Almost on cue, a gentle breeze from the river enveloped me.

My anger pacified.

A sense of magical calm.

Light, beautiful, and fresh everywhere.

I promptly returned to the safer part of the daab. On the farther extreme of the Daab, in big ceramic martaban (jars), was a motley arrangement of raw pickles. A faint smell of raw mounjhe aachar (knol knol pickles), displaced by the light breeze, was lazily floating in the air now. I opened one of the jars carefully and ate the still unripe aachar, giggling with an indescribable happiness.

This one, right here, is one of my happiest childhood memories... my patronous charm. The one I keep going back to – this very scene of looking at expanse of Jhelum, while eating raw pickles, with my back against the coarse, red brick wall of my house.

A distant house on the opposite side of the bank was my favorite. It had the daab projecting right over the river. “It’s like living in a house boat” I had told my father once. After my father explained floods, I realized it’s better to maintain some distance from the river. A few meters from the river, my ancestral house was indeed much better – It was safe.

It took a little more than a year for this assumption to be broken. A jaloos near the masjid threw bricks at our house breaking the beautiful glass panes, shouting “Aazadi ka matlab kya. La illahi ill ill ha”. I hear, the first time they threw a brick, my uncle came out on the daab and shouted back at the mob. The mob did disperse. The gang was bound to come back. And come back they did - a mob of friends, neighbors, and acquaintances joining the loudspeaker on top of the white minaret “raleav (convert), chleav(run), or ghaleav (die)”, marking the Hindu houses in the area, and reviewing the Friday hitlists of Hindus-to-be-killed-this-week pasted on the mosque doors after the Friday namaz.

The three to four Hindu houses among a hundred plus muslim houses in the colony were no defense after all. As the situation worsened, my extended family moved to the safer part of the city – Karan Nagar –perhaps the only Hindu majority area and then later to Badami Bagh, the cantonment area. While we were at Jammu, my grandparents toggled between staying with my uncle in the summer months to escape the scorching heat of the plains and staying with us in the winter.

The next few months of staying in the rented accommodation at Srinagar were extremely difficult for everyone - especially my uncle. He had to buy all household items anew. They had left the house discretely – one by one, not all together.

No one should know we are leaving – the distrust between Hindus and Muslims was light year deep after the female neighbor of a Hindu government servant disclosed his hiding place to militants who were searching for him.

None should know we have left (for as long as possible) – an empty Hindu house was an open invitation for the looters.

Most of all, it was my grandparents who drove him mad by returning to our ancestral house often and at all sorts of time – through the curfews and jaloos which were becoming more and more common now. In their minds, the situation was normal or going to be normal. They had borne the brunt of the Muslim mobs earlier, however the graveness of the situation this time evaded them as it evaded most other Hindu families.

Aush aesh nazaar din ghamit.. (we went to have a look (if everything was ok))

Ghar oush ghandea gomouit (our house had become dirty)

Gas oush khatam gomouit (the gas cylinder had emptied)

The next time my grandfather made a solo cycle trip to get an iron box, my uncle packed their bags and send them to Jammu to stay with us. When they arrived in Jammu, my grandparents, though in their early 50s, had shriveled and aged. As my grandmother emerged from the 10 hour bus journey in a crumpled green saree, she handed me a frilled cloth bag to be keep at a sruooch place (ritually cleaned such as puja rooms or kitchens while fasting). She had travelled the entire journey with the Gods in her lap. I took the cloth bag jiggling with a few Gods from our thokur kuth (puja room) in Srinagar and arranged them as properly as I could in their new residence- our home at Jammu. Our Gods had been forced out too.

As the stay in Jammu moved from an interim arrangement to a more and more permanent one, any news on Kashmir especially the state of our house became an event. At one occasion, a Hindu doctor (or staff - I don’t remember what he exactly did) was kidnapped, blindfolded, and taken to an abandoned Hindu house. Moving through the house, the militants asked him to explain the various pictures of Gods on the walls. He was then taken to a big room, with a line of torture equipment, and asked to strip. Sensing this as his last moments, he expressed his wish to take a leak. The militants asked him mockingly to pee on any on the dead bodies in the bathroom close by. The person could not get himself to pee on the dead and requested to be taken outside. Outside, he saw the Jhelum and realized the house was on the river bank. In the meantime, someone at the hospital had put in a word and he was released without any further physical harm.

My mother was convinced that his description of the JKLF torture center matched exactly that of our house. For a while, this became the sole conversation point - discussed over breakfast, lunch, and dinner. This stopped much later. One day, someone-someone-knew came and mentioned that the tin roof of our house was dismantled and looted. “The house won’t last half a winter. Better to sell it off now while it still fetches some money.”

“That place (Kashmir) is not worth living now (for Hindus)”

I remember the person who came – an old man wearing a stone-colored khan dress and a karakul cap. My mother severed tea in the verandah and asked me to carry the biscuits. As most conversations were at that time, he was speaking to my father about the situation in Kashmir, while my grandfather observed with muted anger from the adjacent chair.

Till our house was sold in late 90s, we never knew if it really was being used as a torture center or was in ruins. Looted it must have been as all other Hindu houses were during that time. I often wonder what would have happened to our house and all our things.

The braer kaenie (attic – used as a store) with its thousand and one secrets – out of bound for the children; the library next to the neel kuth, where I first read Grimm’s fairy tale from a red hard bound book that I still have; the outhouse where my grandfather prepared hookah using an entire paraphernalia of tongs; the garden where we pretend played our fingers being eaten by the evil dog flowers, the dried cherry tree near the plastic tap, the plastic tap which would freeze during winter, and the thousand other knick knacks – dregs from the last 5 generations.

One day, just on a random hunch, I open Google earth. Post many long sessions, I realized that the image resolution and my memories of the Jhelum, our locality – safa kadal, the two temples around our locality, and the idgah were not good enough. I went to my parents with a list of possible matches. While I was focused on finding my house, my parents had a virtual tour of the entire Kashmir. Like a bunch of kids, who have recently being given an Xbox and complete freedom, they went berserk searching for everything – the dal, Shankaracharya, Hari Parbat, the schools and colleges they had attended, the houses of aunts, uncles, and cousins, Gulmarg, Pahalgam, the white ferocious laedher, the calm yarbals on Jhelum - a lifetime of memories relived thanks to Google.

We spoke excitedly for hours that day. They remarked how new localities have sprung where there used to be forests earlier, how the lakes has shrunk to one fourth, and how so many places with their century old Hindu names now had new Islamic tags.

After much meandering, they did find our house. My father snap closed the laptop and asked me not to waste time on it.

Lagnes naar (Let it burn) – reminding me of my grandmother.

I realized that time has not healed Kashmir.

It never will.

Every time I close my eyes to think about my house, I don’t see the happy times – not the Jhelum glowing in the mild sun nor me giggling at the daab. All I see is this recurrent scene of a belligerent mob throwing bricks at our house while my grandmother, shriveled and frail, is closing the planked wooden door of our house. My grandfather, stoic and angry, with an iron box in hand, watching over her curled frame.

Kashmir plays like a broken record – refusing to move to a happier song.

|