Of Sun Disks, World Portals and Medicine Wheels

Of Sun Disks, World Portals and Medicine Wheels – Floater Structures in the Ancient North American Art

By Floco Tausin

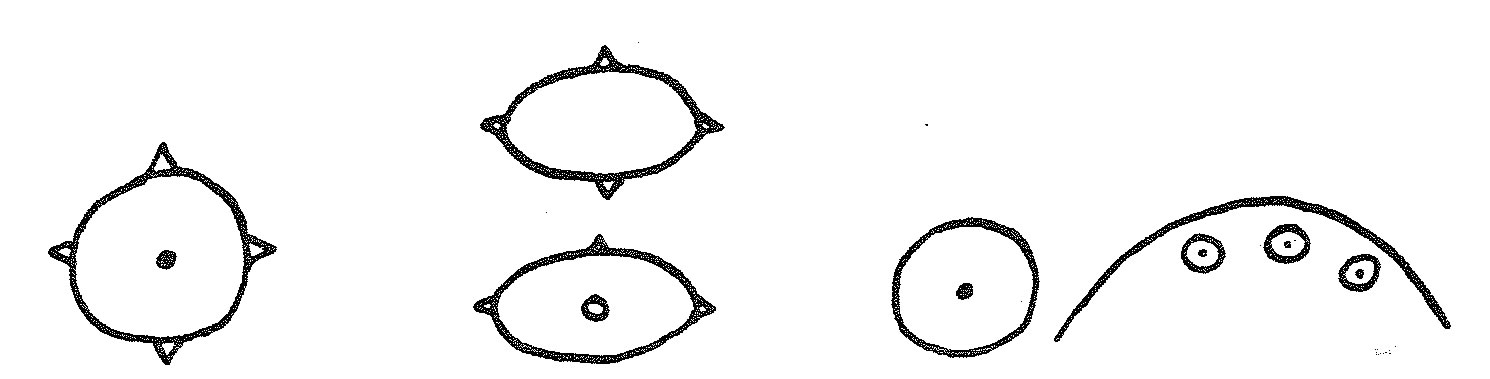

Eye floaters – vitreous opacities or consciousness light? A glimpse into the art and myths of former and non-Western cultures suggests that floaters had a spiritual meaning for many people. This article presents floater motifs and their meaning in North American Indian cultures.This article is based on the experience that a certain type of eye floaters – the “shining structure floaters” – are more than “vitreous opacities,” as ophthalmology claims. This insight came to me by my teacher, the seer Nestor (Tausin 2012a, 2010a, 2009). In my further research, I found numerous indications that floaters – along with other entoptic phenomena – were perceived, artistically reproduced and passed down by the people of many cultures, ancient and modern (e.g. Tausin 2012b, 2012c). They were probably seen during consciousness altering ritual practices and have been mythically or spiritually interpreted (Tausin 2012d, 2010b). This article supports this assumption by presenting floater structures in some of the native cultures of North America. Examples include all of the major cultural regions: the Arctic and Subarctic (Inuit, Yupik), the Northwest Coast (Tlingit), California (Chumash), the Great Basin (Shoshone), the Pueblo cultures of the Southwest, the Algonquian and Sioux tribes of the East and the Great Plains, as well as the Mound Builders of the Southeast.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nordamerikanische_Kulturareale_en.png (5.3.13).

These areas were inhabited by Paleo-Indian hunter-gatherers who had immigrated from Asia in prehistoric times. Various cultures developed from these Paleo-Indians in the Archaic period (c. 10.000-1000 BC). Some of these gradually moved on to agricultural and sedentary lifestyles, forming complex societies. Others remained nomadic hunter-gatherers or practiced hybrid lifestyles. The women and men of these cultures crafted tools, weapons, jewelry and textiles from stone and from products of animals and plants. Some produced ceramics, practiced rock painting or carving and constructed complex sites and earthworks. In the subsequent post-Archaic period (c. 1000 BC until contact with Europeans, 1500-1800 AD), the Native American cultures developed further, but never reached the complexity of the early civilizations in India, China and Europe (cf. Zeitlin 2008; Lynch 2010).

Rock Art

For thousands of years, Native Americans painted or engraved on rocks, mainly in caves, but also on rock walls and boulders outdoors. The designs are figurative – humans or human-like beings, animals, weapons, etc. – or abstract and geometric. Abstract rock art often consists of simple dots, dotted or concentric circles, lines, curves and pit and groove lines (Von Petzinger 2011; Ravilious 2010).

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/coso/gallery.php (28.2.13). Cf. Garfinkel et al. 2009; Hildebrandt/McGuire 2008; Maturango Museum N/A.

What do these circles and lines in Native American rock art signify? According to several theories, they served either mundane or spiritual purposes. They could be a part of mythical stories or memorable events such as travels full of privation or successful military campaigns. Or they could be clan symbols and warning signs that mark boundaries and make territorial claims (Maturango Museum n / a; Colton, 1960). They could also refer to hunting magic rituals, which were thought to magically increase the hunting success and ensure the game animals’ return from the underworld (cf. Garfinkel 2006). Perhaps they were part of some group rituals or rites of passage, e.g. to restore the celestial power balance and thus ensure cosmic stability, or to renew the world (Woollaston 2013; Hadingham 1984; Hudson/Underhay 1978). Another explanation, supported by today’s Native Americans, is that the dotted and concentric circles represent celestial bodies, the sun, the moon or particular stars (cf. Colton 1960). Finally, the dots and lines are seen as examples of geometric motifs that represent entoptic phenomena, which supposedly had been seen by the Natives during shamanic rituals while under the influence of hallucinogens. In this sense, the concentric circles of the Chumash or Shoshone could be an allusion to the shamanic flight (Dowson/Lewis-Williams 1988; cf. Garfinkel/Austin 2011; Garfinkel 2006; Whitley 2005, 1994; Winkelman 2004; Furst 2004; Rätsch 1998; Roach 1998; Whitley 1994; Thurston, 1991; Wellman, 1978; Gerber 1975).

Crafts

The dotted circles and lines motifs are not limited to rock art, but are seen on pieces of art made from a variety of materials like stone, bone, ivory, wood, leather, shells, clay and metal.

In Native American crafts, we find spheres, circles and lines or tubes not only as motifs for decoration, but they were creatively implemented in pottery, carving, and architecture as well. Pottery vessels, for example, were decorated on the inner surface, but often the bottom was left blank. Seen from above, they appear as spheres with a core and a surround.

Another example are the perforated disks from stone or shells that have been found across North America. What they were intended for is unknown (cf. Kipfer 2007, Morse/Morse 1983).

Native American cultures are also known for their use of beads, made from stone, bone, horn, metals, but mainly shells. Beads are perforated and mostly shaped as disks, spheres and tubes, other forms are less frequently.

For thousands of years, beadworks in North America are not just jewelry, but are also used as a popular commodity, a form of currency, and as documents of diplomacy. For Native Americans, the single beads also have a spiritual meaning, insofar as they are a reminder of and key to the world of the spirits. For example, present-day Algonquian-speaking Natives explain that the knowledge of the Wampum – the traditional white and purple shell beads of the Eastern Woodland tribes – was given to them by beings of light from the sky. The beads represent „little lights, little spirits, and little prayers.” This is exemplified by the beads’ white color, as well as their ability to light up and glow in the dark due to the shells’ phosphorus content. In addition, the beads are associated with the stars and other celestial bodies (Aubin 1996; Neil-Binion 2013).

Architecture and earthworks

The Pueblo cultures of the Southwest are known for their architectural achievements. One example is their houses which were dug into the ground and roofed over with layers of wood and mud. Mostly circular in shape, these pit-houses could be entered through a tunnel on the side, but more commonly through a hole in the roof. Since the 9th century, the Pueblos also used special pit-houses as ceremonial rooms, so-called Kivas. According to creation myths, kivas reflect the round sky, but also have a hole in the ground, the portal to the Underworld (sipapu), through which the ancestors and spirits (kachinas) emerged to enter our world (Taylor 2012). Today, the kivas still serve as a meeting place for men and as place for ritual purposes.

In the northeastern Plains, numerous circles of boulders and stones laid down on the ground have been discovered. Such stone circles lie in the grasslands, but also on the ground of river beds, river terraces and on the fringe of the highland. They appear individually, or in groups of several dozens or even hundreds. Most are simple rings of a few meters in diameter, sometimes with a central cairn.

In addition to these smaller rings there are much larger stone circles, which are referred to as “medicine wheels.” They consist at least of a central cairn and an outer ring of stones. More complex forms have several circles and “spokes” radiating from the central cairn.

Medicine wheels were often constructed over several generations who used them for different purposes like ceremonies, dances, healing and teaching. According to a Crow legend, medicine wheels were places of feasting and vision quests (Lynch 2010). Some researchers also suggest that the early stone structures had calendrical and astronomical functions and were used to determine the time of festivals and ceremonies (Kelley 2008; Vickers 1992-93). Today, New Age and other alternative religious uses of medicine wheels are widespread (e.g. Sun Bear/Wabun 1980; cf. Harvey/Wallis 2007).

For a long period of time, much of the eastern parts of North America were dominated by the Mound Builders. These cultures – e.g. Adena (c. 1000 BC to 200 AD), Hopewell (c. 200 BC to 700 AD) and Mississippian (c. 700 to 1600 AD) – are known to have built mounds of different size, height and shape. They are often flat-topped or rounded cones, but also appear in the shapes of pyramids or even animals (effigy mounds). Like the medicine wheels, the mounds were built over generations. They were not simply piled up, but consist of several layers of earth and stones, shells, bones, human remains, charcoal and various other objects and materials.

Some of the mounds are isolated, but often they are found in various village sites. Here, they are arranged in circles or connected to each other by ridges. The most ancient of these sites were found along the Ohio, the Mississippi and several smaller rivers in Louisiana. Dated to the fifth millennium BC, they are the first monumental sites of North America. Examples of archaic mound sites are Watson Brake (Louisiana) and Sapelo Island (Georgia), but mounds were built until the collapse of the Mound Builder cultures due to the contact with Europeans.

The significance of the mounds and ridges is unclear. Probably, some of the mounds were just kitchen middens (Marquardt 2010). Others might have served as protection from enemies and floods (Thornton 2011). The arrangements of several mounds in particular sites suggest their use for astronomical observation (Taylor 2012; Kelley 2008). Furthermore, excavations of the mounds revealed human remains and objects without any evident use. This suggests that these mounds were used as burial grounds: They were piled up over the burnt down mortuary chamber. Then another chamber was constructed and, after the funeral, was again covered with mud and other materials etc. Other mounds again have obviously served as platforms for gatherings and rituals, and for temples and the dwellings of the elite (Young/Fowler 2000; O’Connory 1995).

Floaters in ancient Native American cultures – an entoptic interpretation

Over and over again, the ancient cultures of North America have depicted the shapes of dotted or concentric circles and lines or tubes. These shapes were painted or engraved on rock walls, shells and pottery. They were crafted as donut stones and stone disks, used as beads for beadwork, laid down as stone circles, implemented in the construction of buildings and villages sites. All of these forms were created by different Native American cultures at different times for different purposes. Therefore, there are multiple interpretations of the meaning of these shapes, mundane as well as spiritual. Most of the time, though, we don’t get clear answers about why these forms were used.

If present-day Native Americans are asked about the meaning of their ancestors’ art, they often resort to their traditional knowledge and stories in order to explain. Widespread and recurring motifs in Native American creation myths are the three cosmic layers – sky, earth and underworld –, the spirit world as well as the celestial bodies. For example, the Shasta of California and Oregon believe that the creator Chareya bored a hole in the sky, descended through it to the earth where he created life. The creation myths of the southwestern cultures tell about four Underworld caves, one upon each other, through which the ancestors traveled until they have reached the earth’s surface. An Apachean myth tells about a stairway that leads to a hole or entrance to the sky. The Pawnee of Nebraska believe that the creator Tirawahat arranged the marriage between the evening star and the morning star whose children created the earth. The Natives of the Eastern Woodlands tell about how the omnipotent sun created the universe and the living beings using its rays. According to a creation myth of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), there is a tree of light in the sky whose flowers illuminated the earth. Then the humans dug up the roots of the tree so that the tree disappeared through a hole and the world darkened (Taylor 1995; Mooney 1987; Johnston 1979; Müller 1956; Curtin 1922; Parker 1912).

What these myths have in common is a close relationship between floater structures and mythic themes such as cosmic spheres or spirits and celestial bodies with creative functions: Life is created from spherical or circular structures or bodies, there is movement through holes, openings or tubes, while “ladders” and “trees” – shapes similar to floater (dotted) tubes – connect the cosmic spheres (cf. Tausin 2012d). Not surprisingly, the symbolic depictions of the cosmic layers, the spirits and the celestial bodies – as we know from anthropological research – look like floaters, too. In the Eskimo-Aleut and Na-Dene cultures of the Arctic and Subarctic, dotted and concentric circles generally symbolize the passage into another world. For example, the Yupik use a dotted circle to designate the ellam iinga, the “eye of awareness.” It symbolizes the spiritual activity and marks the presence of the “little soul” which has special powers of perception and consciousness. The places that are marked with this symbol are considered as passages into the Other World where spiritual and medical knowledge can be obtained (Arevgaq John 2010; Walter/Fridman 2004). Similarly, the ovoids of the Northwest Coast Indians symbolize the openings or passages through which the soul vanishes to the Other World when a person is sick or dies. According to the belief of many Northwest Coast tribes, the soul leaves the body not only through the orifices, but also through the joints. This is why ovoids are depicted not only as eyes, but also as joints (Canadian Museum 2010).

In the Mississippian culture of the Southeast, a dotted circle – often accompanied by petals – represents the sky or Upper World. The cross in a circle, known from many Native American cultures, is associated with the sun and symbolizes the sacred fire on earth. The Swastika-like cross in a circle refers to the Underworld, while the ogee motif in a circle represents the passage into that world. The central or world axis is depicted as a column often with dotted circle or ogee motif in the center (Reilly/Garber 2007; cf. Woollaston 2013; Morgan 1980).

In the Algonquian and Sioux tribes of the East and the Plains, circles with central dot or crosses indicate spirits or spiritual powers. Such powers can manifest in natural phenomena or in humans, animals, plants and other non-human beings and cause goods and bads, success or failure, healthiness or sickness. Since they are mysterious and unpredictable, they are treated with respect and appeased with ritual offerings. The Algonquian collectively call these spiritual powers “Manitou” or – if thought as primary or supreme spiritual power – “Kitchi Manitou” (“Great Spirit”). Related concepts are “Orenda” (Iroquois) and “Wakan” (Sioux) (cf. Haefeli 2007).

Spiritual powers are also associated with the celestial bodies, which play an important role in many or all Native American cultures. When Natives observed the sun, the moon and the stars, they didn’t do it in the modern astronomical sense. The Chumash, for example, associated the celestial bodies with mythic subjects, hallucinogenic plants, social affairs and individual health, among other things. The celestial bodies were seen as spiritual powers that had to be ritually appeased, begged for their return, or reconciled in order to keep up the cosmic balance (cf. Hadingham 1984; Hudson/Underhay 1978). In particular, sun and moon were depicted as dotted or concentric circles, often with rays or petals.

It seems probable then, that the concentric or dotted circles of the ancient Native American rock art, crafts, architecture and earthworks likewise refer to spirits, the Other World – particularly the Upper World –, and passages between these cosmic worlds. If that is correct, why are such mythic elements depicted as dotted and concentric circles, partly combined with tubular structures? I suggest that these structures are inspired by shining structure floaters that were seen and interpreted by the ancient Native Americans. Certainly, there must have been many opportunities to notice floaters in the day sky. But if they were worthy to be remembered in the myths and the arts, they must have been experienced in special and meaningful circumstances where the observers were more sensitive to celestial phenomena. For example, floaters could have been seen while gazing at the day sky – e.g. at the sun and its course, or at certain meteorological or celestial phenomena – in order to look for signs of the spirits (cf. Hudson/Underhay 1978). Or they were perhaps seen during vision quests and shamanic rituals, often supported by altered states of consciousness and hallucinogens (Rätsch 1998; Walter/Fridman 2004; cf. Tausin 2012d). Visions were sought especially by young men as a part of their initiation and in order to gain a spirit helper. The vision seeker went to a lonely place in the mountains, the woods or the desert where he fasted, stayed awake as long as possible, prayed and performed various physical and mental exercises. He waited and watched for a sign of the spirits (Walter/Fridman 2004). In all these unusual situations, shining structure floaters could have been seen and understood e.g. as companions of the sun, as a gift or message of the spirits, as celestial gates or openings to the Other World, as world axis, or simply as spirits. Looking at accounts and depictions of dreams and visions, these symbols appear again. Taking an example of the Ojibwa and Cree, the visionary follows the path from the right (1), sees the earth at first, then the stars and the moon (2), then follows the path to Manitou’s home (3), then ascends to a ring that contains four dots (4) from which Manitou sends the four winds (Müller 1956).

Once the shining structure floaters have entered the cultural repertoire, they could be repeatedly carved, painted, crafted or constructed, perhaps in order to indicate the corresponding locations or states in messages and memories, to ritually pay tribute to the spirit world, or to ward off unfavorable powers or events. While being passed down through space and time, these signs were most probably further developed, combined with other motifs, expressed through various styles, enhanced or altered in their original meaning. This explains the numerous variations of the dotted or concentric circles and lines or tubes. But what these motifs do suggest is that there are seers among the ancient and modern Native Americans who see shining structure floaters at certain times and in certain circumstances and have given them a spiritual meaning.

References:

The pictures are taken from image hosting websites, from scientific publications (online and print) and/or from my own collection (FT). Either they are licensed under a Creative Commons license, or their copyright is expired, or they are used according to the copyright law doctrine of ‘Zitatrecht,’ ‘fair dealing’ or ‘fair use.’

Arevgaq John, Theresa (2010): Yuraryararput Kangiit-Llu: Our ways of dance and their meanings (Thesis, University of Alaska Fairbanks).

http://ankn.uaf.edu/Curriculum/PhD_Projects/Arevgaq/Yuraryaraput_Kangiit-llu.pdf (8.12.14)Aubin, Claude (1996): Wampumpeag: The Spiritual Science of the Wampum Belts.

http://claudeaubinmetis.com/viewtopic.php?f=32&t=277 (18.11.14)Austin, Don (2003-2013): Petroglyphs.us.

http://www.petroglyphs.us/ (6.11.14)Beuchat, H. (1912): Manuel D’Archéologie Américaine. Paris

Bostrom, Peter A. (2011): Cogged Stones & Cactus Sclices. 7,500 to 5,000 Years Ago Southern California.

http://lithiccastinglab.com/gallery-pages/2012coggedstonespage1.htm (1.10.14)Bouchet-Bert, Luc (1999): From Spiritual and Biographic to Boundary-Marking Deterrent Art: A Reinterpretation of Writing-on-Stone. In: Plains Anthropologist 44, no. 167: 27-46

Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation (2010). Haida Art.

http://www.civilization.ca/cmc/exhibitions/aborig/haida/haaar01e.shtml (22.3.13)Colton, Harold S. (1960): Black Sand. Prehistory in Northern Arizona. University of New Mexico Press

Curtin, Jeremiah (1922): Seneca Indian Myths.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/nam/iro/sim/index.htm (21.3.13)Dowson, T. A.; Lewis-Williams, J. D. (1988). The Signs of All Times. In: Current Anthropology 29, no. 2: 201-245

Eastern States Rock Art Research Association (ESRAR).

http://esrara.org/ (6.11.14)Fienup-Riordan, Ann (2000): Eye fo the Dance: Spiritual Life of the Central Yup’ik Eskimos. In: Native Religions and Cultures of North America. Anthropology of the Sacred, hg. v. Lawrence E. Sullivan. News York/London: Continuum

Finnigan, James T. (1982): Tipi Rings and Plains Prehistory: A Reassessment of Their Archaeological Potential. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada

Fitzhugh, William W. (2008): Arctic and Circumpolar Regions. In: Encyclopedia of Archaeology, 3 Bde., hg. v Deborah M. Pearsall. Academic Press: 247-271

Furst, Peter T. (2004): Visionary Plants and Ecstatic Shamanism. In: Expedition 46, No. 1: 26-29.

http://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/46-1/Visionary%20Plants.pdf (13.3.13)Garfinkel, Alan P.; Austin, Donald R. (2011): Reproductive Symbolism in Great Basin Rock Art: Bighorn Sheep Hunting, Fertility and Forager Ideology. In: Cambridge Archaeological Journal 21, no. 3: 453-471

Garfinkel, Alan P. u.a. (2009): Myth, ritual and rock art. Coso decorated animal-humans and the Animal Master. In: Rock Art Research 28, no. 2: 179-197.

http://www.petroglyphs.us/article_myth_ritual_and_rock_art.htm (20.11.14)Garfinkel, Alan P. (2006): Paradigm Shifts, Rock Art Studies, and the „Coso Sheep Cult“ of Eastern California. In: North American Archaeologist 27, no. 3: 203-244

Gebhard, David (1966): The Shield Motif in Plains Rock Art. In: American Antiquity 51, no. 5: 721-732

Gerber, Peter (1975): Die Peyote-Religion nordamerikanischer Indianer. Eine kulturanthropologische Interpretation (Dissertation). Zollikon: A. Wohlgemuth

Hadingham, Evan (1984): Early Man and the Cosmos. Walker

Haefeli, Evan (2007): On First Contact and Apotheosis: Manitou and Men in North America. In: Ethnohistory 54, no. 3: 407-443

Hartley, Ralph J. (2011): Rock Art. In: Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, hg. v. David J. Wishart. University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.art.053(6.11.14)Harvey, Graham; Wallis, Robert J. (2007): Historical Dictionary of Shamanism (Historical dictionaries of Religions, Philosophies, and Movements, 77). Lanha u.a.: The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Hildebrandt, W. R.; McGuire, K. R. (2008): Great Basin. In: Encyclopedia of Archaeology, 3 Bde., hg. v. Deborah M. Pearsall. Academic Press: 290-300

Hoffman, Walter James (1897): The Graphic Art of the Eskimo. Washington: Government Printing Office

Hudson, Travis; Underhay, Ernest (1978): Crystals in the Sky: An Intellectual Odyssey Involving chumash Astronomy, Cosmology and Rock Art (Anthropological Papers 10): Ballena Press

Johnston, Basil (1979): Und Manitu erschuf die Welt. Mythen und Visionen der Ojibwa. Köln/Düsseldorf: Eugen Diederichs

Kelley, David H. (2008): Archaeoastronomy. In: Encyclopedia of Archaeology, 3 Bde., hg. v. Deborah M. Pearsall. Academic Press: 451-464

Keyser, James D. (1977): Writing-on-Stone: Rock Art on the Northwestern Plains. In: Canadian Journal of Archaeology 1: 15-80

Keyser, James D. (1975): A Shoshonean Origin for the Plains Shield Bearing Warrior Motif. In: Plains Anthropologist 20, no. 69: 207-215

Kipfer, Barbara Ann (2007): Dictionary of Artifacts. Blackwell

Koerper, Henry C. u.a. (2007): An Unusual Donut-Shaped Artifact from CA-LAN-62. In: Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 43, no. 4. 75-88.

http://www.pcas.org/documents/donut-shapedartifact434.pdfLink, Adolph W. (1980): Discoidals and problematical stones from Mississippian sites in Minnesota. In: Plains Anthropologist 25, no. 90: 343-352

Lynch, Patricia Ann (2010): Native American Mythology A to Z. Chelsea House.

Marquardt, William H. (2010): Shell Mounds in the Southeast: Middens, Monuments, Temple Mounds, Rings or Works? In: American Antiquity 75, no. 3: 551-570

Maturango Museum (n/a): Coso Petroglyph Landmark – Archaeology, Ethnography, and Rock Art.

http://www.maturango.org/Resources/Coso%20Petroglyph%20Description.pdf(18.3.13)Mooney, James (1987): Myths of the Cherokee. 19th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology 1897-98, Part I.

Morgan, William N. (1980): Prehistoric Architecture in the Eastern United States. Cambridge/London: The MIT Press

Morse, Dan F.; Morse, Phyllis A. (1983): Archaeology of the Central Mississippi Valley. New York: Academic Press

Müller, Werner (1956): Die Religionen der Waldindianer Nordamerikas. Berlin: Reimer

Neil-Binion, Denise 2013: The Delaware Indians and the development of Prairie-style beadwork (MA-Thesis, University of New Mexico.

https://repository.unm.edu/bitstream/handle/1928/23204/Dec%204%202012%20Denise%20Neil-Binion%20Thesis%20Final.pdf?sequence=1 (18.11.14)O‘Connor, Mallory (1995): Lost Cities of the Ancient Southeast. University Press of Florida

Parker, Arthur C. (1912): Certain Iroquois Tree Myths and Symbols. In: American Anthropologist 14, no. 4: 608-620

Pauketat, Timothy R. (2008): Eastern Woodlands. In: Encyclopedia of Archaeology, 3 Bde., hg. v Deborah M. Pearsall. Academic Press: 279-289

Rätsch, Christian (1998): Enzyklopädie der psychoaktiven Pflanzen. AT Verlag

Ravilious, Kate. (2010). The writing on the cave wall. New Scientist 2748

Reed, Paul F. (2008): American Southwest, Four Corners Region. In: Encyclopedia of Archaeology, 3 Bde., hg. v Deborah M. Pearsall. Academic Press: 231-247.

Reilly, F. Kent; Garber, James F. (Hg.) (2007): Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms. Interpretations of Mississippian Iconography. University of Texas Press

Roach, Mary (1998): Ancient Altered States. What do squiggles, dots, and spirals on rock walls mean? Ask your local shaman – or archeologist Dave Whitley. In: Discover 19, no. 6.

http://www.discover.com/issues/jun-98/features/ancientalteredst1456/(21.6.06)Rogers, Hugh C. (2003): The Shield Bearing Warrior in Navajo Era Rock Art. In: Kiva 68, no. 3: 247-269

Royal Alberta Museum (2013): What is a Medicine Wheel?

http://www.royalalbertamuseum.ca/research/culturalStudies/archaeology/faq.cfm (21.11.14).Simek, Jan F. u.a. (2013): Sacred landscapes of the south-eastern USA: prehistoric rock and cave art in Tennessee. In: Antiquity 87: 430-446

Sun Bear/Wabun (1980): The Medicine Wheel: Earth Astrology. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc./Englewood Books

Sundstrom, Linea; Keyser, James D. (1998): Tribal Affiliation of Shield Petroglyphs from the Black Hills and Cave Hills. In: Plains Anthropologist 43, no. 165: 225-238

Tausin, Floco (2012a): Eye Floaters (EF) and other subjective visual phenomena.

http://www.eye-floaters.info/floaters/subjective-visual-phenomena.htm (30.9.14)Tausin, Floco (2012b): From Prehistoric Shamanism to Early Civilizations: Eye Floater Structures in Ancient Egypt. In: International Journal of Healing and Caring (IJHC) 12, no. 2.

http://www.wholistichealingresearch.com/122tausin(3.12.14)Tausin, Floco (2012c): Shamash, Ishthar and Igigi – Floater structures in ancient Mesopotamia. In: Ovi Magazine, August 10, 2012.

http://www.ovimagazine.com/art/8990 (3.12.14)Tausin, Floco (2012d): Lights from the Other World – Floater structures in the visual arts of modern adn present-day shamans. In: New Age Spirituality, May 15, 2012.

http://new-age-spirituality.com/wordpress/content/2209 (3.12.14)Tausin, Floco (2010a): Eye Floaters. Floating spheres and strings in a seer’s view. In: Holistic Vision 2.

http://www.eye-floaters.info/news/news-june2010.htm (3.12.14)Tausin, Floco (2010b): Entoptic phenomena as universal trance phenomena. In: Paranormal Underground 3, issue 11.

http://issuu.com/paranormalunderground/docs/november_2010_paranormal_underground (3.12.14)Tausin, Floco (2009): Mouches Volantes. Eye Floaters as Shining Structure of Consciousness, Leuchtstruktur Verlag: Bern

Taylor, Colin (1995): Die Mythen der nordamerikanischen Indianer. München: Beck

Taylor, Ken (2012): Celestial Geometry. Understanding the Astronomical Meanings of Ancient Sites. London: Watkins Publication

Thornton, Richard (2011): Were mounds originally built to protect Native Americans from floods? Examiner.com.

http://www.examiner.com/article/were-mounds-originally-built-to-protect-native-americans-from-floods#ixzz1NO4dh8fn (18.11.14)Thurston, Linda (1991): Entoptic Imagery in People and their Art. MA thesis, faculty of the Gallatin Division, New York University.

http://home.comcast.net/~markk2000/thurston/thesis.html (26.7.11)Turpin, Solveig A. 2005: Location, Location, Location: The Lewis Canyon Petroglyphs. In: Plains Anthropologist 50, no. 195: 307-328

Vickers, J. Rod (1992-93): Medicine Wheels: A Mystery in Stone. In: Alberta Past 8 (3): 6-7.

Von Petzinger, Genevieve (2011). Geometric Signs. A new understanding.

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/geometric_signs/geometric_signs.php (13.2.12)Walsh, Michael R. (2008): California and the Sierra Nevada. In: Encyclopedia of Archaeology, 3 Bde., hg. v Deborah M. Pearsall. Academic Press: 271-279

Walter, Mariko Namba and Fridman, Eva Jane Neumann (2004): Shamanism – An Encyclopedia of World Beliefs, Practices, and Culture. Santa Barbara et al.: ABC Clio.

Wedel, Waldo Rudolph (1961): Prehistoric man on the Great Plains. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press

Wellmann, Klaus F. (1978): North American Indian Rock Art and Hallucinogenic Drugs. In: JAMA 239, no. 15: 1524-1527

Whitley, David S. (2005): The Iconography of Bighorn Sheep Petroglyphs in the Western Great Basin. In: Onward and Upward!, Papers in Honor of Clement W. Meighan, hg. v. Keith L. Johnson. Chico: Stansbury Publishing: 191-203

Whitley, David S. (1994): By the Hunter, for the Gatherer: Art, Social Relations and Subsistence Change in the Prehistoric Great Basin. In: World Archaeology 25, no. 3: 356-373

Winkelman, Michael (2004): North America – Overview. In: Shamanism – An Encyclopedia of World Beliefs, Practices, and Culturem hg. v. Mariko Namba Walter und Eva Jane Neumann Fridman. Santa Barbara et al.: ABC Clio: 275-279

Wormington, Hannah Marie (1961): Prehistoric Indians of the Southwest. Denver: Denver Museum of Natural History

Woollaston, Victoria (2013): America’s oldest cave paintings found, dating back six thousand years. Mail Online, 18.6.13.

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2343766/American-cave-rock-art-lay-hidden-SIX-THOUSAND-YEARS-offers-unique-remarkable-insight-Native-American-societies-lived-lives.html (27.10.14)Young, Biloine; Fowler, Melvin (2000): Cahokia: The Great Native American Metropolis. University of Illinois Press

Zeitlin, Robert N. (2008): Early Cultures of Middle America. In: Encyclopedia of Archaeology, 3 Bde., hg. v Deborah M. Pearsall. Academic Press: 162-182

Floco Tausin

The name Floco Tausin is a pseudonym. The author received a PhD at the Faculty of the Humanities at the University of Bern, Switzerland. In theory and practice, he is engaged in the research of subjective visual phenomena in connection with altered states of consciousness and the development of consciousness. In 2009, he published the mystical story “Mouches Volantes” about the spiritual dimension of eye floaters. floco.tausin@eye-floaters.info www.eye-floaters.info The book:‚Mouches Volantes. Eye Floaters as Shining Structure of Consciousness‘.

(Spiritual Fiction. ISBN: 978-3033003378. Paperback, 15.2 x 22.9 cm / 6 x 9 inches, 368 pages).

Floco Tausin tells the story about his time of learning with spiritual teacher and seer Nestor, taking place in the hilly region of Emmental, Switzerland. The mystic teachings focus on the widely known but underestimated dots and strands floating in our field of vision, known as eye floaters or mouches volantes. Whereas in ophthalmology, floaters are considered a harmless vitreous opacity, the author gradually learns about them to see and reveals the first emergence of the shining structure formed by our consciousness. »Mouches Volantes« explores the topic of eye floaters in a much wider sense than the usual medical explanations. It merges scientific research, esoteric philosophy and practical consciousness development, and observes the spiritual meaning and everyday life implications of these dots and strands.

»Mouches Volantes« – a mystical story about the closest thing in the world..